55 Years Ago: Nine Months Before the Moon Landing

In October 1968, the American human spaceflight program took significant steps toward achieving President John F. Kennedy’s goal of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth before the end of the decade. American astronauts returned to space after a 23-month hiatus. The success of the 11-day Apollo 7 mission heralded well for NASA to decide to send the next mission, Apollo 8, to orbit the Moon in December. The Saturn V rocket for that flight rolled out to its seaside launch pad two days before Apollo 7 lifted off. Preparations for later missions to test the Lunar Module (LM) in Earth orbit and around the Moon continued in parallel, as did work in anticipation of astronauts and their lunar samples returning from the Moon. Meanwhile, the Soviet Union also resumed its human spaceflight program.

Left: Apollo 7 astronauts Donn F. Eisele, left, Walter M. Schirra, and R. Walter Cunningham review flight trajectories with Director of Flight Crew Operations Donald K. “Deke” Slayton shortly before launch. Middle: Schirra, left, Eisele, and Cunningham suit up for launch. Right: Liftoff of Apollo 7, returning American astronauts to space!

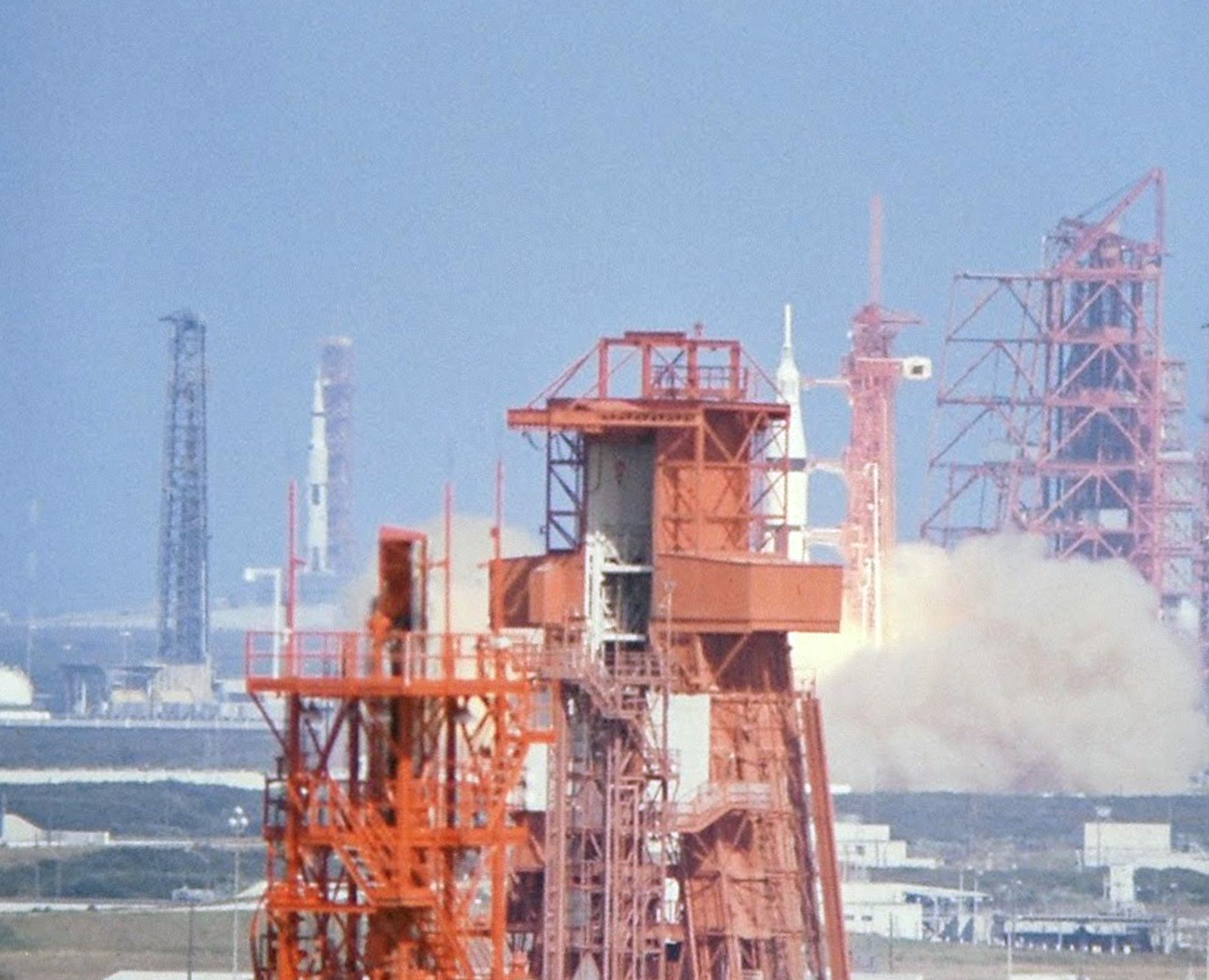

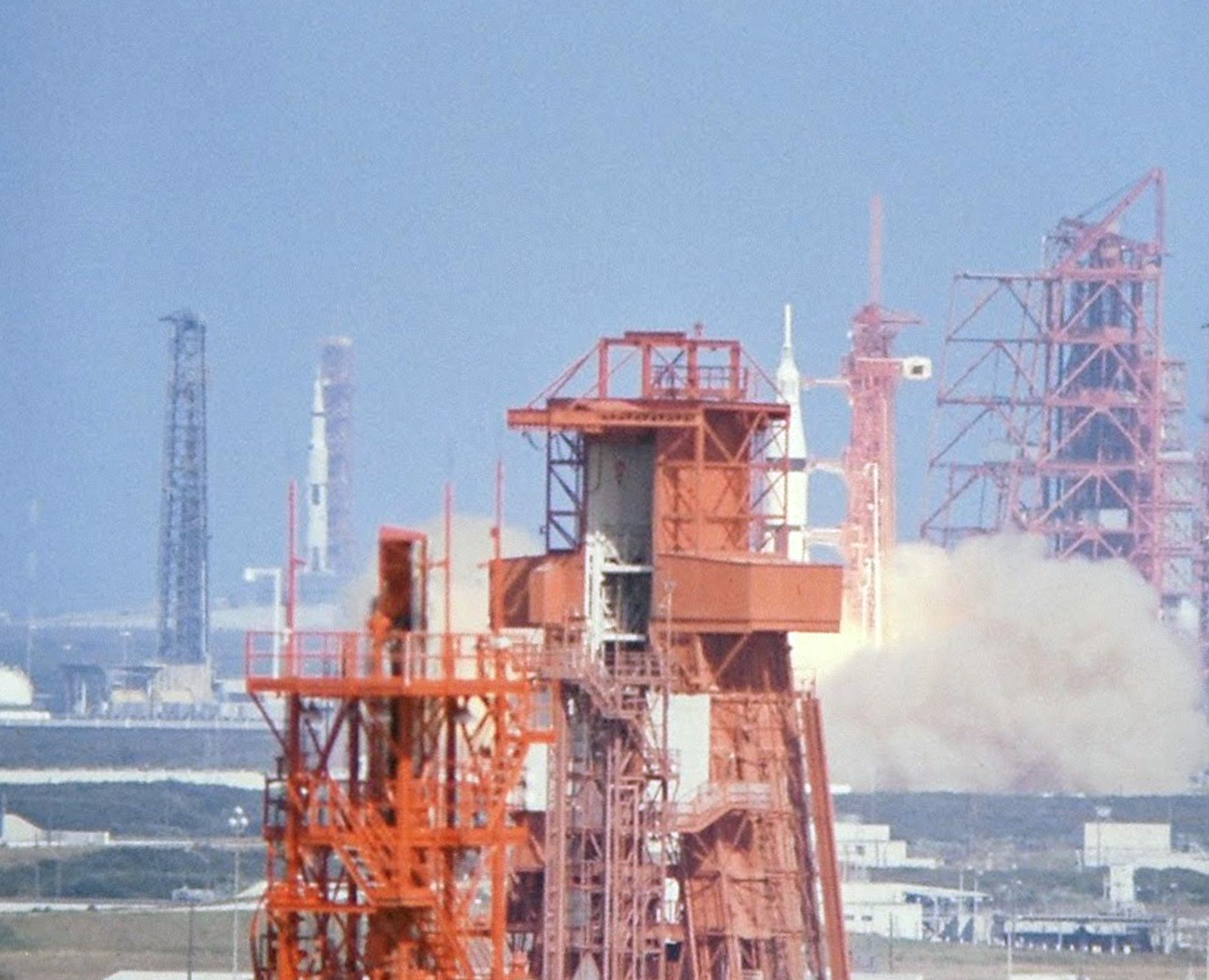

The liftoff of Apollo 7 astronauts Walter M. Schirra, Donn F. Eisele, and R. Walter Cunningham on Oct. 11, 1968, signaled the end of a 23-month hiatus in American human spaceflights resulting from the tragic Apollo 1 fire. To prevent a recurrence of the fire and to increase overall safety, NASA and North American Rockwell in Downey, California, redesigned the Apollo spacecraft, and Schirra, Eisele, and Cunningham spent months training to test it in Earth orbit. By the time they lifted off from Launch Pad 34 at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida, the Saturn V rocket for the Apollo 8 mission had already rolled out to Launch Pad 39A a few miles away.

Left: View of Apollo 7 lifting off from Launch Pad 34, with the Saturn V for Apollo 8 on Launch Pad 39A in the background. Middle: The Apollo 7 S-IVB third stage, used as a rendezvous target. Right: Apollo 7 astronauts Donn F. Eisele, left, Walter M. Schirra, and R. Walter Cunningham on the prime recovery U.S.S. Essex following their successful 11-day mission.

During their 11-day mission, Schirra, Eisele, and Cunningham thoroughly tested the redesigned Apollo spacecraft. Early in the mission, they performed rendezvous maneuvers with their rocket’s S-IVB second stage, a maneuver planned for later missions to retrieve the LM. They thoroughly tested the Service Propulsion System engine, critical on later lunar missions for getting into and out of lunar orbit, by firing it on eight occasions, including the critical reentry burn to bring them home. The three astronauts conducted the first live television broadcasts from an American spacecraft, providing viewers on the ground with tours of their spacecraft. Teams from the U.S.S. Essex (CV-9) recovered Schirra, Eisele, and Cunningham and their Command Module (CM) from the Atlantic Ocean on Oct. 22. Apollo program managers declared that Apollo 7 “accomplished 101%” of its planned objectives.

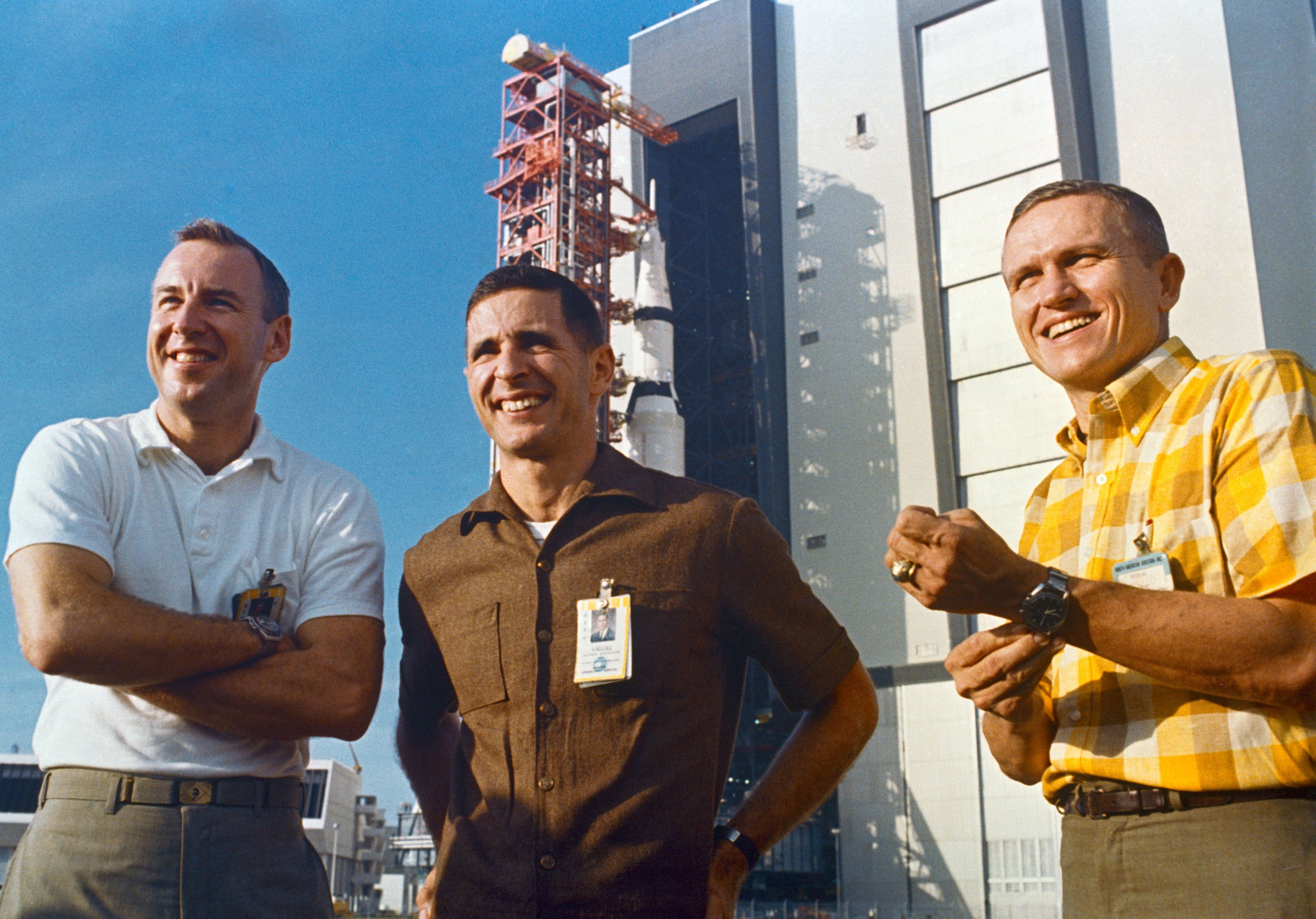

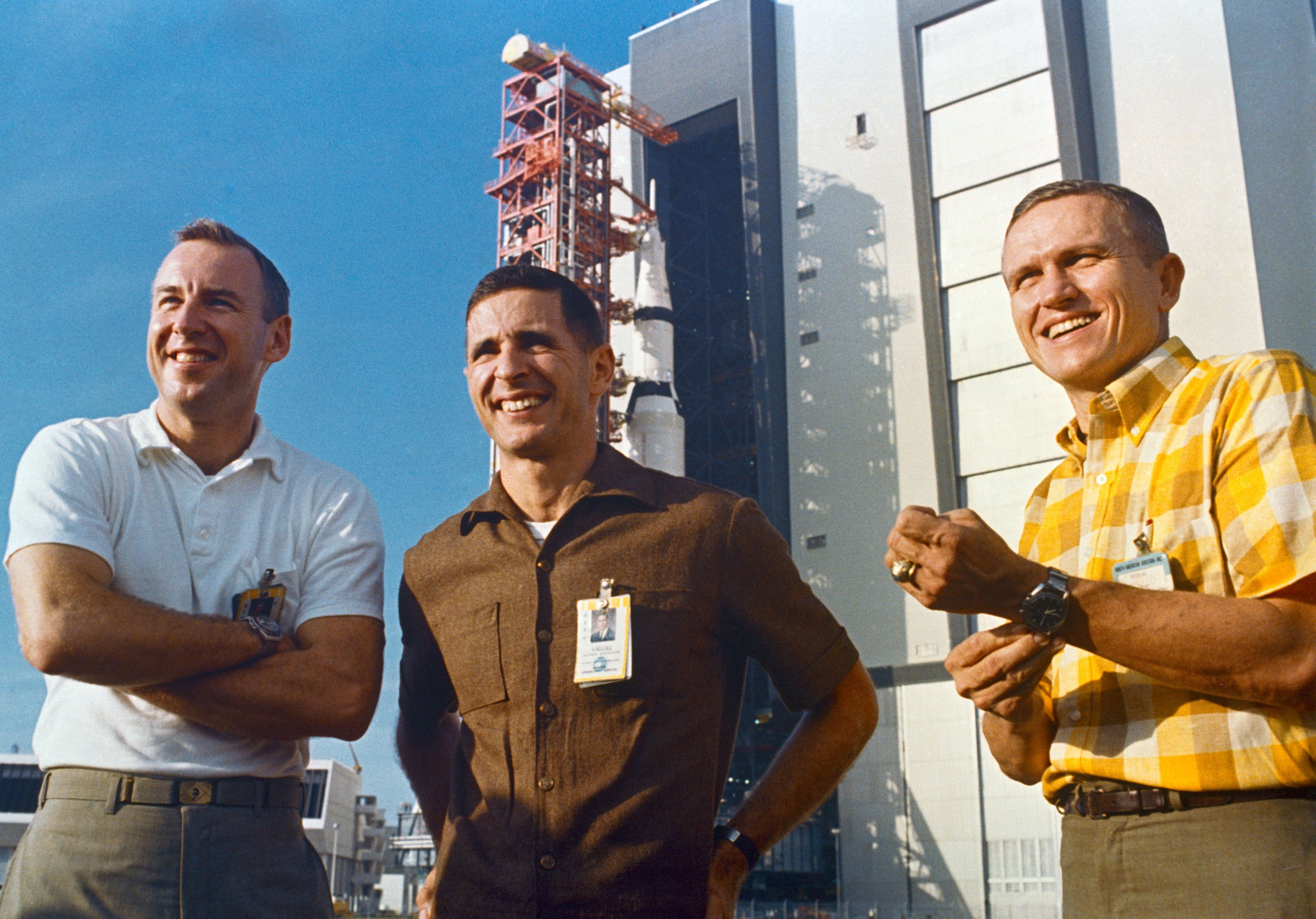

Left: Apollo 8 astronauts James A. Lovell, left, William A. Anders, and Frank Borman attend the rollout of their Saturn V from the Vehicle Assembly Building to Launch Pad 39A. Middle: The Apollo 8 Saturn V at Launch Pad 39A. Right: Borman, left, Lovell, and Anders pose with their Saturn V following a crew egress exercise from their spacecraft.

The success of Apollo 7 gave NASA the confidence to announce in November that the next mission, Apollo 8, would attempt to enter orbit around the Moon. In early October, workers in High Bay 2 of KSC’s Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) completed the stacking of the Saturn V rocket for Apollo 8 by adding the Command and Service Module (CSM). On Oct. 9, two days before Apollo 7 lifted off, as the Apollo 8 crew of Frank Borman, James A. Lovell, and William A. Anders and other NASA officials looked on, the completed Saturn V rolled out from the VAB to begin its eight-hour journey to Launch Pad 39A, three and a half miles away. After the rocket arrived at the pad and engineers began testing it, on Oct. 23, Borman, Lovell, and Anders suited up and practiced emergency egress from the spacecraft, as did their backups Neil A. Armstrong, Edwin E. “Buzz” Aldrin, and Fred W. Haise.

Left: Apollo 8 astronauts Frank Borman, left, William A. Anders, and James A. Lovell on the deck of the M/V Retriever prepare for their water egress test. Middle: Anders, left, Lovell, and Borman inside the boilerplate Apollo spacecraft during the water egress test. Right: Anders, left, Lovell, and Borman in the life raft after egressing from their spacecraft.

As part of their training, Borman, Lovell, and Anders conducted water egress training in the Gulf of Mexico near Galveston, Texas. On Oct. 25, sailors aboard the Motor Vessel M/V Retriever lowered a mockup CM with the crew inside into the water in a nose-down position. Flotation bags inflated to right the spacecraft to a nose-up position. The astronauts then exited the capsule onto life rafts and recovery personnel hoisted them aboard a helicopter. The next day, backups Armstrong, Aldrin, and Haise repeated the test.

Left: Workers in the Vehicle Assembly Building at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida lower the S-IVB third stage onto the S-II second stage during stacking operations of the Apollo 9 Saturn V. Middle: Apollo 9 astronaut Russell L. Schweickart practices entering and leaving the Command Module while wearing a pressure suit during brief periods of weightlessness aboard a KC-135 aircraft. Right: Engineers conduct a docking test between the Apollo 9 CM, bottom, and Lunar Module in an altitude chamber in KSC’s Manned Spacecraft Operations Building.

Preparations for Apollo 9 included training for the first spacewalk of the Apollo program. According to the mission plan, with the LM and CM docked, crew members in both spacecraft would open their hatches. During the spacewalk, one astronaut would transfer from the LM to the CM using handrails for guidance and enter the CM in a test of an emergency rescue capability. The training for this activity took place aboard a KC-135 aircraft from Patrick Air Force Base (AFB) in Florida. By flying repeated parabolic trajectories, the aircraft could simulate 20-30 seconds of weightlessness at a time, during which the astronauts wearing space suits practiced entering and exiting a mockup of the CM. Backup crew members Alan L. Bean and Richard F. Gordon completed the training on Oct. 9 followed by David R. Scott and Russell L. Schweickart of the prime crew the next day. North American Rockwell delivered the Apollo 9 CSM to KSC in early October. At the end the month, technicians in KSC’s Manned Spacecraft and Operations Building (MSOB) conducted a docking test of the Apollo 9 LM and CSM to verify the interfaces between the two vehicles. In the VAB’s High Bay 3, workers stacked the three stages of the Saturn V rocket for Apollo 9 during the first week of October.

Left: Workers in the Manned Spacecraft Operations Building (MSOB) at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida uncrate the Apollo 10 Lunar Module (LM) descent stage shortly after its arrival. Middle: MSOB workers unwrap the Apollo 10 LM ascent stage. Right: MSOB workers prepare to mate the Apollo 10 LM ascent stage to its descent stage.

In preparation for Apollo 10, planned as a test of the CSM and LM in lunar orbit, the Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation in Bethpage, New York, delivered the LM for that mission to KSC. The descent stage arrived Oct. 11, followed by the ascent stage five days later. Technicians in the MSOB mated the two stages and installed the assembled vehicle into a vacuum chamber on Nov. 2 to begin a series of altitude tests.

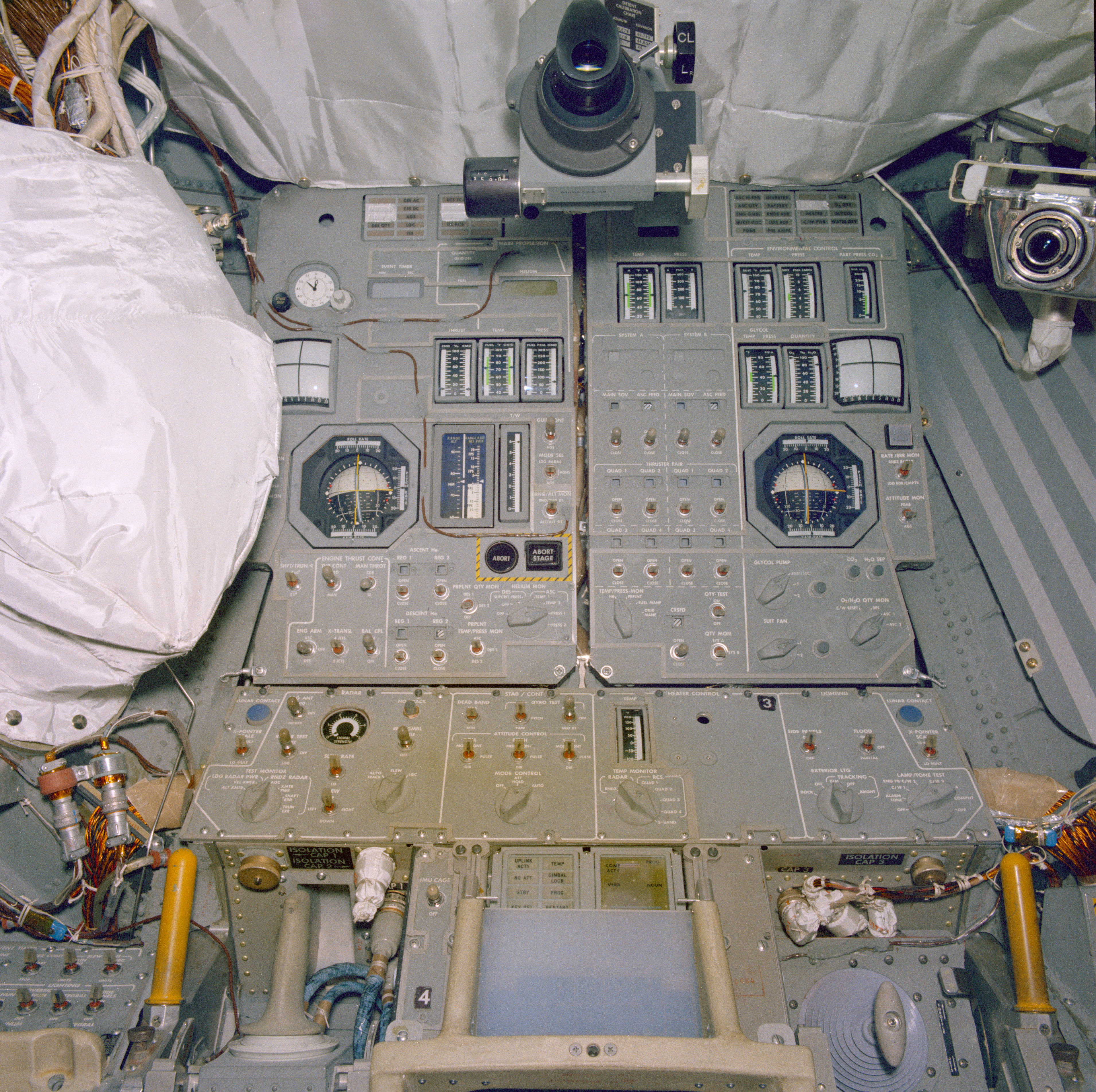

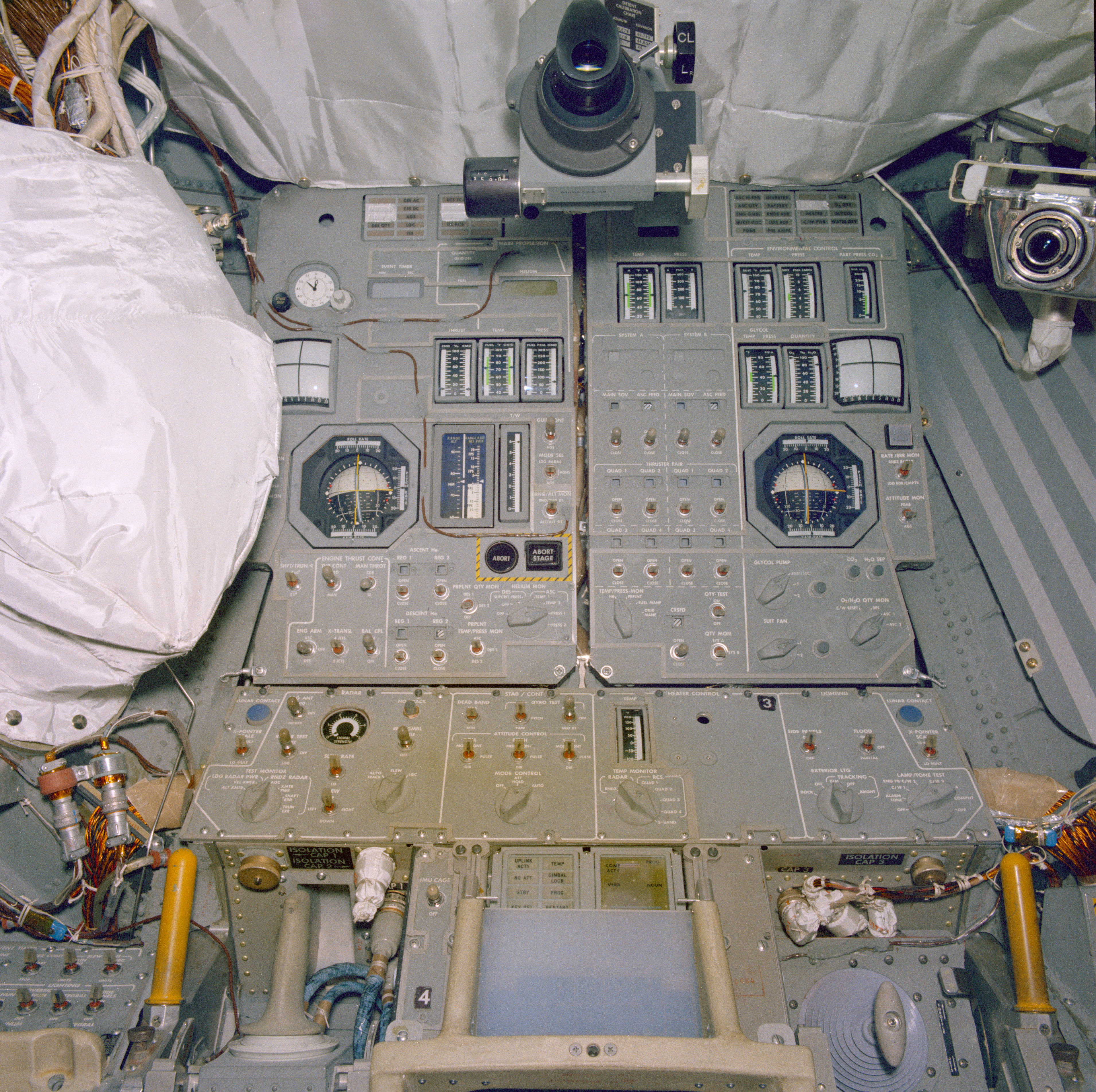

Left: A flight of the Lunar Landing Training Vehicle at Ellington Air Force Base in Houston. Middle: The forward instrument panel of the Lunar Module Test Article-8. Right: Richard Wright, administrative assistant for the Lunar Receiving Laboratory, gives astronaut Michael Collins a tour of the gloveboxes for examining lunar samples.

The Lunar Landing Training Vehicle (LLTV), built by Bell Aerosystems of Buffalo, New York, allowed Apollo astronauts to master the intricacies of landing on the Moon by simulating the LM’s performance in the final few hundred feet of the descent to the surface. Although an excellent training tool, the LLTV and its predecessor the Lunar Landing Research Vehicle (LLRV) also carried some risk. Astronaut Armstrong ejected from an LLRV on May 6, 1968, moments before it crashed at Houston’s Ellington AFB. The final accident investigation report, issued on Oct. 17, cited a loss of helium pressure that caused depletion of the fuel used for the reserve attitude thrusters, with inadequate warning to the pilot as a contributing factor. By that time, Chief of Aircraft Operations Joseph S. “Joe” Algranti piloted the properly modified LLTV during its first flight on Oct 3. Algranti and NASA pilot H.E. “Bud” Ream completed 14 checkout flights before a crash in December grounded the LLTV. In October, NASA began a series of critical thermal-vacuum tests to certify the Apollo LM for lunar missions. The tests, conducted in the Space Environment Simulation Laboratory (SESL), at the Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC), now NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, involved Grumman pilots Gerald P. Gibbons and Glennon M. Kingsley and astronaut James B. Irwin. The tests using Lunar Module Test Article-8, concluded in November, and simulated the temperatures expected during a typical flight to the Moon and descent to the surface.

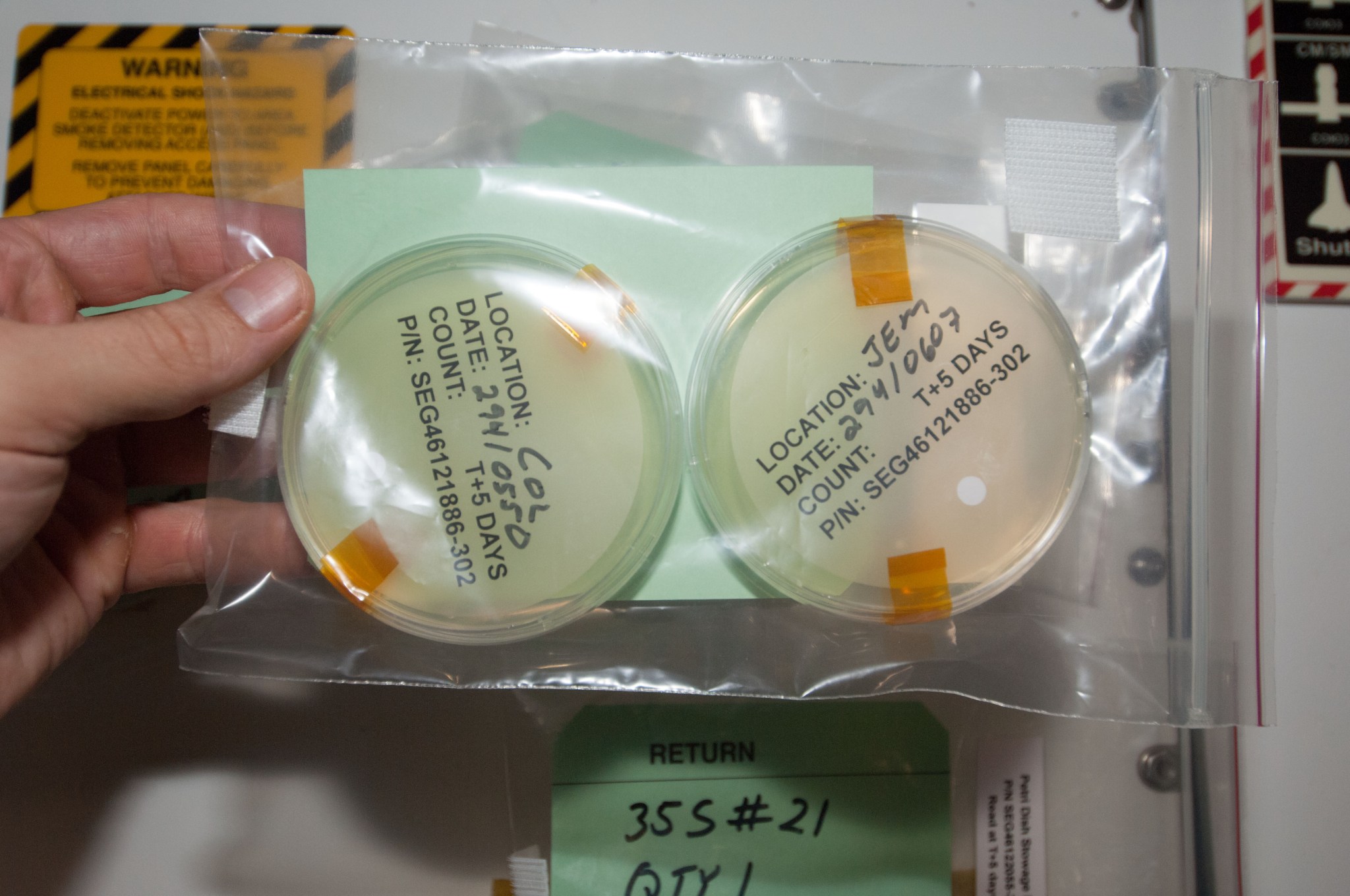

To receive astronauts and their lunar samples after their return from the Moon, NASA built the Lunar Receiving Laboratory (LRL) in MSC’s Building 37. The LRL’s special design isolated astronauts and rock samples returning from the Moon to prevent back-contamination of the Earth by any possible lunar micro-organisms. By October 1968, with the Moon landing likely less than a year away, the LRL had reached a state of readiness that warranted a simulation of some its capabilities. Between Oct. 22 and Nov. 1, managers, scientists, and technicians carried out a 10-day simulation of LRL operations following a lunar landing mission. Although the exercise uncovered many deficiencies, enough time remained to correct them before the actual Moon landing.

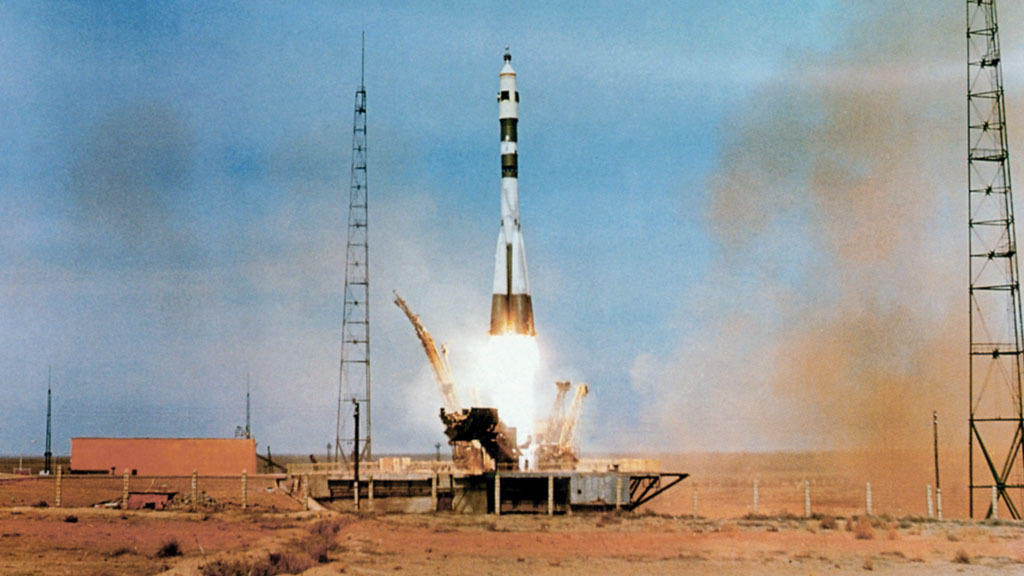

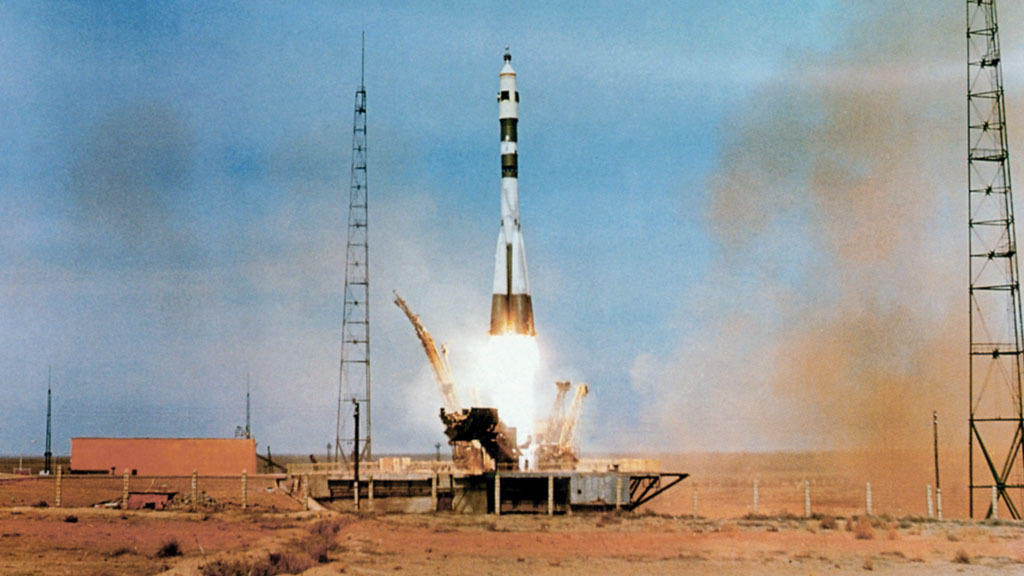

Left: Lift off of Soyuz 3 from the Baikonur Cosmodrome carrying cosmonaut Georgi T. Beregovoi. Middle: Beregovoi during a television broadcast from Soyuz 3. Right: The Soyuz 3 spacecraft carrying Beregovoi descends under its parachute for a soft-landing. Image credits: courtesy Roscosmos.

As a reminder that a race to the Moon still existed, the Soviet Union also resumed crewed missions, halted in April 1967 by the death of Soyuz 1 cosmonaut Vladimir M. Komarov. Just three days after the Apollo 7 splashdown, the Soviets launched Soyuz 2, but without a crew. The next day, Soyuz 3 lifted off with cosmonaut Georgi T. Beregovoi aboard, at 47 the oldest person to fly in space up to that time. Although Beregovoi brought the two spacecraft close together, he could not achieve the intended docking. Soyuz 2 landed on Oct. 28 and Beregovoi in Soyuz 3 two days later. Following the Zond 5 circumlunar flight in September, rumors persisted that the next Zond mission may soon carry two cosmonauts on a similar circumlunar flight. The apparently successful Zond 5 mission coupled with the rumors of an imminent Soviet crewed lunar mission possibly contributed to the decision to send Apollo 8 on its historic circumlunar flight in December 1968.

News from around the world in October 1968:

Oct. 2 – Redwood National Park established to preserve the tallest trees on Earth.

Oct. 7 – The Motion Picture Association of America adopts a film rating system.

Oct. 12 – Equatorial Guinea gains independence from Spain.

Oct. 12 – The XIX Olympic Games open in Mexico City, the first time the games held in Latin America.

Oct. 14 – The Beatles finish recording the double “White Album.”

Oct. 16 – The Jimi Hendrix Experience releases its last studio album “Electric Ladyland.”

Oct. 17 – Release of the film “Bullitt,” starring Steve McQueen.

Oct. 20 – American high jumper Dick Fosbury introduces the Fosbury Flop technique at the Mexico City Olympics.

Oct. 24 – The 199th and last flight of the X-15 hypersonic rocket plane takes place at Edwards Air Force Base in California, piloted by NASA pilot William H. Dana.

Oct. 25 – Led Zeppelin gives its first concert, at Surrey University in England.

Powered by WPeMatico

Get The Details…

Kelli Mars