The Future is Bright: Johnson Space Center Interns Shine Throughout Summer Term

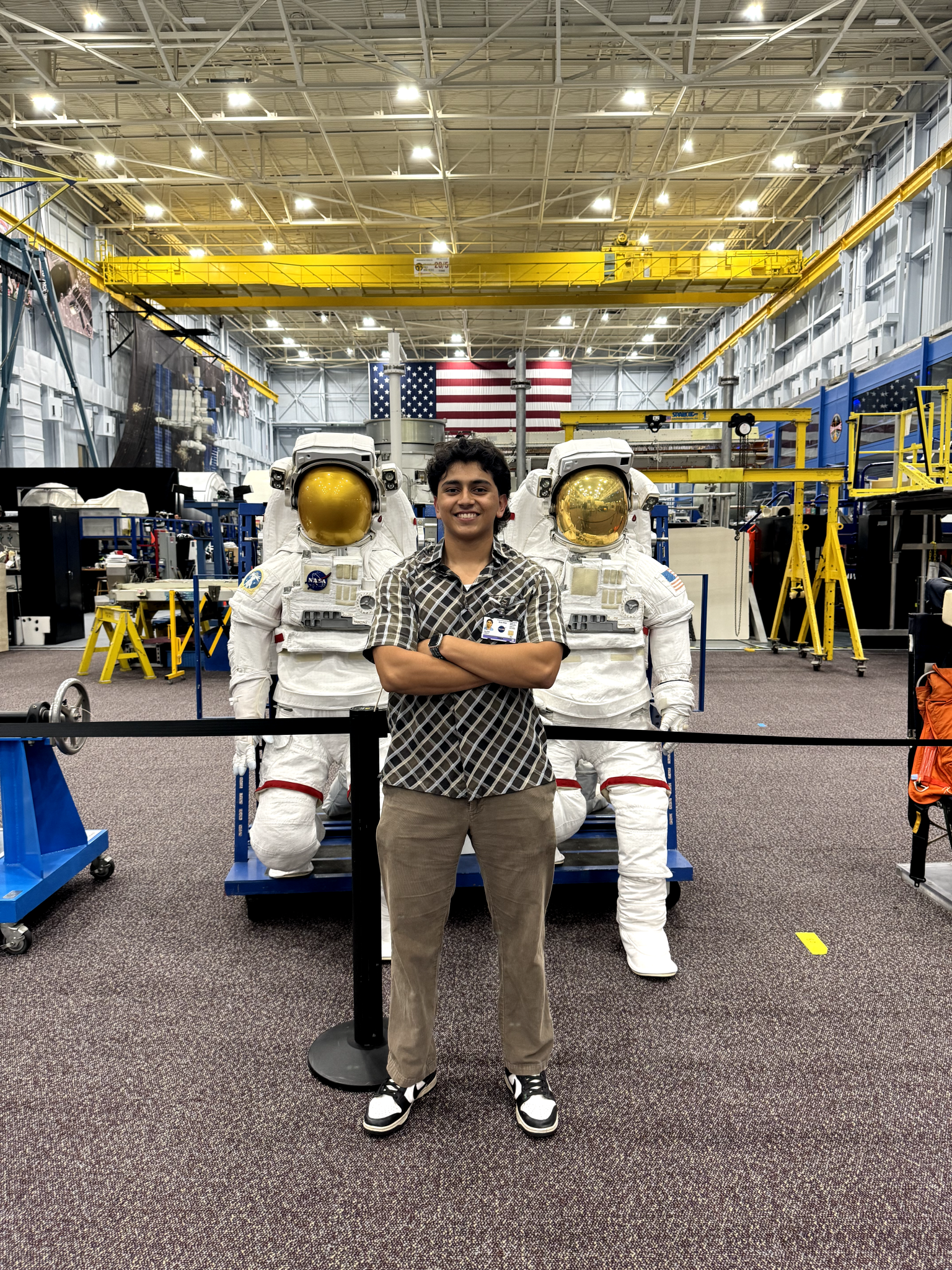

More than 100 interns supported operations at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston this summer, each making an important impact on the agency’s mission success. Get to know seven stellar interns nominated by their mentors for their hard work and outstanding contributions.

Stella Alcorn

Assignment: Engineering Directorate, Guidance, Navigation, and Control Autonomous Flight Systems Branch, Orion Program

Education: Aeronautical and Astronautical Engineering, Purdue University; graduating May 2026

Proudest internship accomplishment: Learning a new software program and applying topics I learned in school to develop a dynamic overlay display prototype for Orion Rendezvous, Proximity Operations, and Docking. My eagerness to learn and support from my mentor and colleagues has allowed me to make great progress on writing code to enable new display prototyping capabilities to support future Artemis missions.

Important lesson learned: Ask questions and engage with coworkers because you don’t gain valuable skills or experience without putting yourself out there. It can be nerve-wracking to collaborate with new people, but I have learned that taking initiative opens a gateway of opportunities.

Advice for incoming interns: Get to know other interns, go to NASA events, don’t be afraid to reach out or ask questions to your mentor, peers, or superiors (even if they’re not in your office or branch). This internship is a privilege, and you should take advantage of all available opportunities. Make connections and learn, but also have fun!

Laila Deshotel

Assignment: Safety and Mission Assurance Directorate, Space Habitation Systems Division, Computer Safety and Software Assurance Branch

Education: Mechanical Engineering, University of Texas at San Antonio; graduating 2026

Proudest internship accomplishment: Being of service to the International Space Station and Gateway Programs. I contributed to JAXA’s (Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency) unmanned cargo vehicle, the HTV-X, as a Computer-Based Control Systems (CBCS) safety reviewer. This involves understanding CBCS requirements, reviewing hazard reports in the given safety data package, and attending safety review panels. I am also assisting with the software safety and assurance for Gateway.

Important lesson learned: This term allowed me to see the results of taking initiative and networking with others for professional development outlets. When you aren’t stepping outside of your comfort, you don’t allow any room for further improvement.

Advice for incoming interns: Channel your passion for space into productive work by taking initiative and staying organized. Network actively, seek feedback, embrace learning opportunities, be adaptable, and maintain a positive attitude to make the most of your internship and pave the way for a successful career.

Hunter Kindt

Assignment: Safety and Mission Assurance Directorate, Space Habitation Systems Division, Computer Safety and Software Assurance Branch

Education: Mechanical Engineering, University of Wyoming; graduating December 2024

Proudest internship accomplishment: I am performing a hazard analysis on a spacesuit for armadillos for my exit presentation project. This was inspired by my “Texas to-do list” for the summer, which included seeing an armadillo. I also love iced coffee, and, for fun, I created a cartoon of an armadillo in a spacesuit drinking iced coffee. All of us at the safety review panel I was supporting had a good laugh about it, and it led to a conversation about the logistics of an armadillo in a spacesuit. This project demonstrates my ability to apply the knowledge I have learned during my internship, specifically in safety, to any situation accurately.

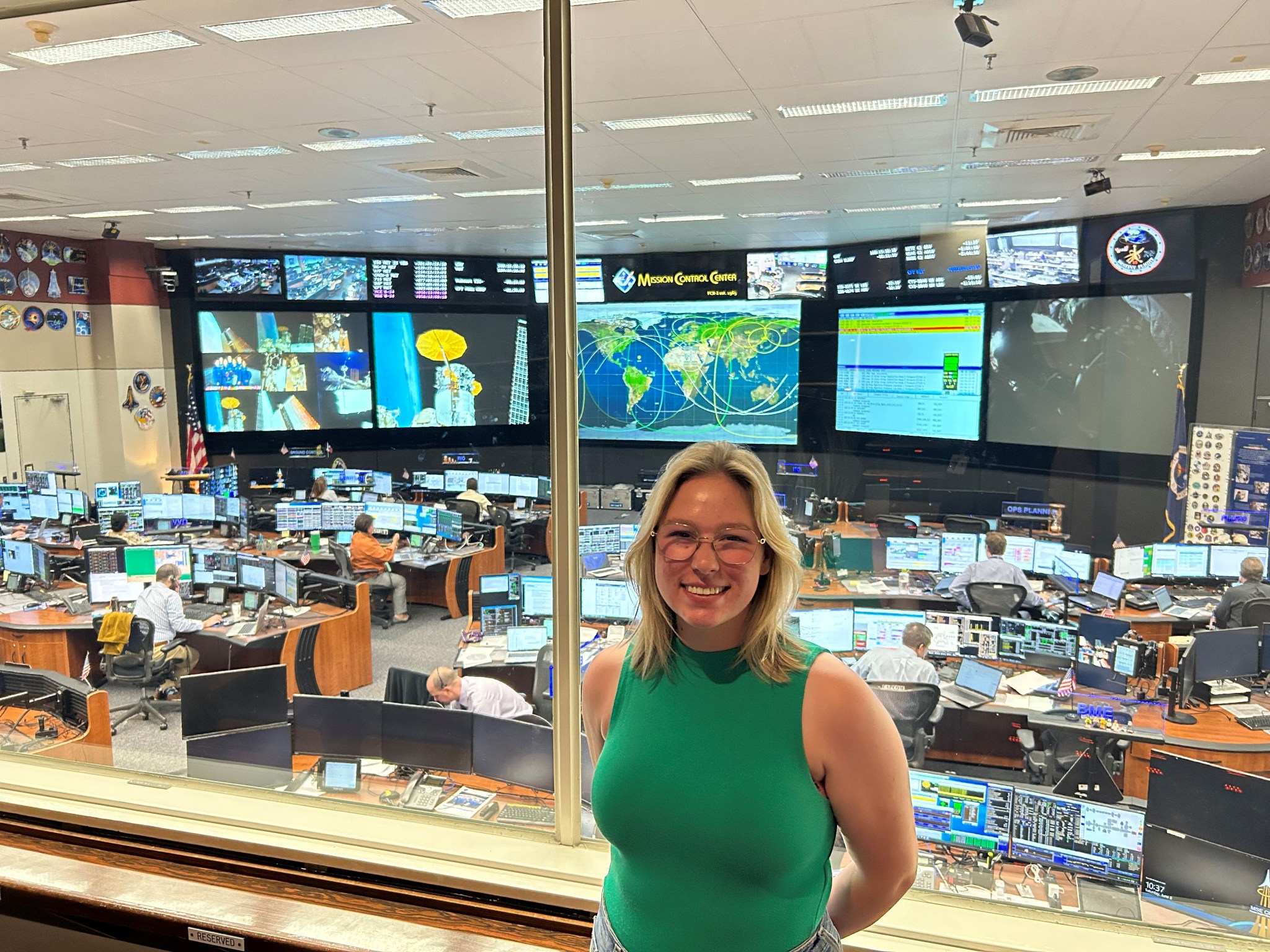

Favorite Johnson experience: On a professional level, it was the ability to work with JAXA personnel during the safety review panel for their new HTV-X. Working and building connections with international partners is an experience I will never forget! On a personal level, it was touring the Mission Control Center and seeing the sun rise and set live from the International Space Station!

Advice for incoming interns: Say yes to any opportunity you are presented with.

Mia Garza

Assignment: Office of Communications

Education: Marketing, University of Houston’s Bauer School of Business; graduating December 2024

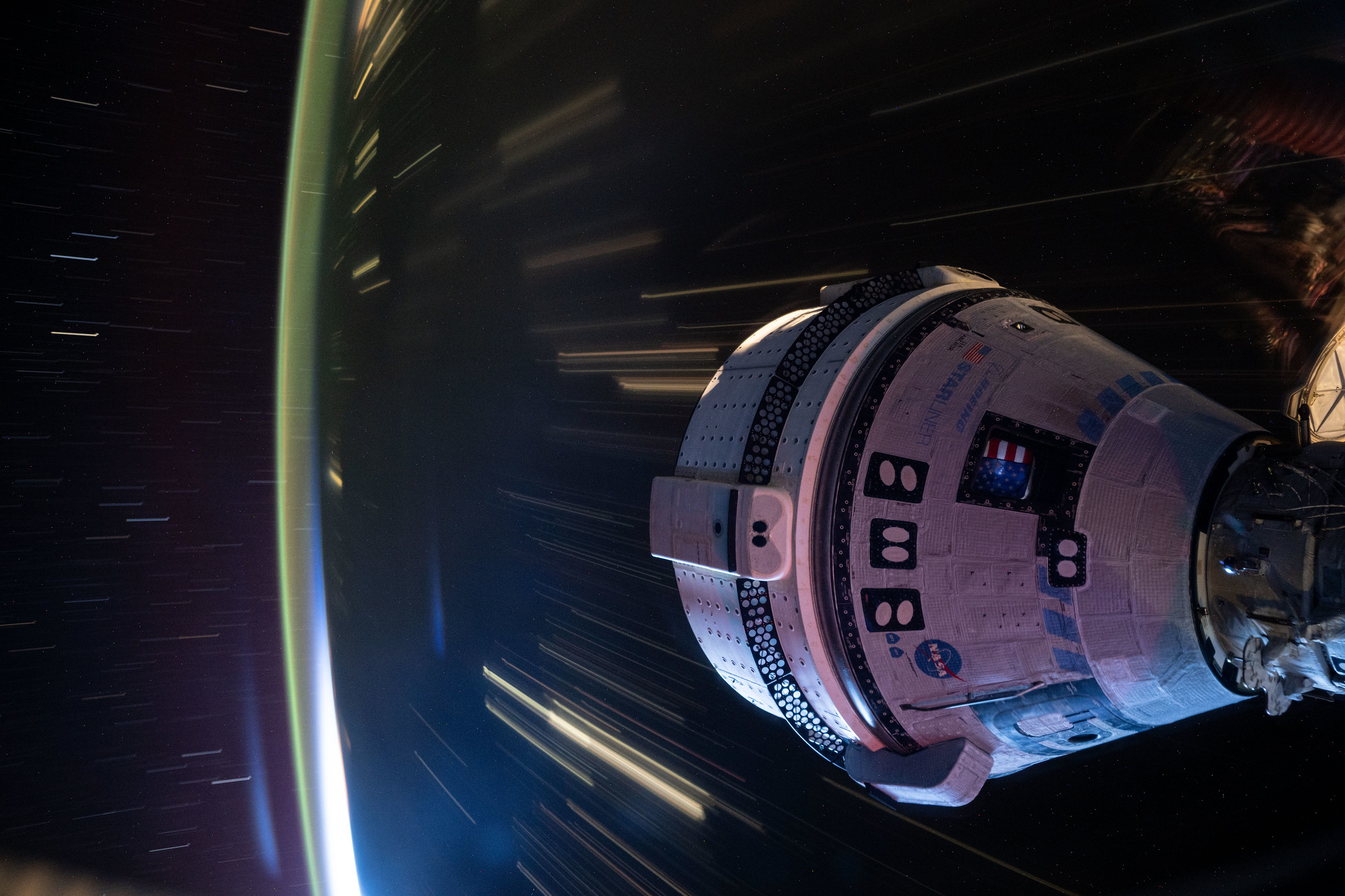

Proudest internship achievement: My intern project of creating and executing an employee engagement plan for NASA’s Boeing Crew Flight Test (CFT). I worked with two other interns to create a unique plan to get the Johnson workforce excited about the CFT launch. We created custom crew drinks with RoyalTEA & Coffee Co., held a crew sendoff event which also included a poster decorating party for employees, hosted CFT booths at center-wide events, and hung ‘Godspeed, Suni and Butch’ banners around campus. We ended the project with a fun viewing event for employees and their families.

Favorite Johnson experience: Planning the building 12 dedication that happened on July 19. The tasks have varied between planning the seating chart, writing scripts, and helping create the run of show for the event. But getting to experience the planning process of this event and seeing it come to life has been a surreal experience.

Important lesson learned: The true power of teamwork. It takes a village to accomplish all of the great things that happen here.

Yosefine Santiago-Hernandez

Assignment: Safety and Mission Assurance Directorate, Space Habitation Systems Division, Computer Safety and Software Assurance Branch

Education: Mechanical Engineering, University of Puerto Rico-Mayaguez; graduating May 2027

Proudest internship accomplishment: Serving as lead representative for CBCS in a safety review panel of an International Space Station payload.

Favorite Johnson experience: Working while surrounded by space history. There is always something going on, and something to see. It has been incredible to tour places like the Mission Control Center, Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory, and vacuum chambers. Also, it was pretty cool to meet an astronaut from my home country, Puerto Rico.

Important lesson learned: To persevere and step out of my comfort zone. I am working on concepts I have not worked on previously and are not taught in the classroom, therefore it has been a challenge to learn about them and contribute to the work. I took this challenge with a positive attitude and have been able to gain further understanding of systems engineering and CBCS and complete my tasks.

Courtney Thompson

Assignment: Center Operations Directorate, Logistics Division and Director’s Office

Education: Supply Chain Management, University of Nebraska-Lincoln; graduated December 2023

Proudest internship achievement: Getting here! Working at NASA was always the dream, though it didn’t seem like that was going to happen for me. I went back to school as a nontraditional business student a few years ago. I thought that would work against me but rolled the dice and here I am. Both my spring and summer internship mentors have been incredibly supportive during my time here. Temporary or not, this has been one of the best experiences of my life.

Important lesson learned: Remember what we are a part of. There are so many amazing things humanity has accomplished; many of those things are right here at NASA. Tour the facilities, ask questions, watch the launches, and celebrate and share with your friends. We are so lucky to get to witness these things up close and be a part of that history.

Advice for incoming interns: Always ask questions. Someone else probably has that question, too, or has never thought of things that way. It also helps show initiative and gets people to learn your name. Have a crazy new idea for something? Ask if it’s been done before or if it’s even feasible. And if they love the idea, you might just find more people to help make it happen.

Luis Valdez

Assignment: Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning – Software Development for Decision Intelligence Capability, Office of the Chief Information Officer’s Information, Data, and Analytics Services Team

Education: Computer Science, Texas A&M University; graduating May 2026

Proudest internship achievement: I’m proud of how much I’ve been able to learn and get done as the only intern on my project. It was pretty daunting at first, but I also saw it as an opportunity to show what I have to offer. Also, networking with other interns, civil servants, and even other companies like Google has been a dream come true.

Important lesson learned: Everything always changes. At the beginning of my internship, there was no clear path for me to take to achieve our objective, so it was all up to me to make the vision come to life. If something wasn’t working out, or if the customer wanted something different that wasn’t possible, I changed my methods to make it possible.

Advice for incoming interns: Get involved. Let yourself integrate fully into this internship. It’s a once-in-a-lifetime experience and working at NASA has been the dream of millions of people so make sure you take it all in. Also, connect with your mentor! They have so much to offer, and they truly want the best for you.

Powered by WPeMatico

Get The Details…

Linda E. Grimm