55 Years Ago: Eight Months Before the Moon Landing

November 1968 proved pivotal to achieving the goal of landing a man on the Moon before the end of the decade. The highly successful Apollo 7 mission that returned American astronauts to space provided the confidence for NASA to decide to send the next flight, Apollo 8, on a trip to orbit the Moon in December. At NASA’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida, the Saturn V rocket and the Apollo spacecraft for that mission sat on Launch Pad 39A undergoing tests for its upcoming launch. In the nearby Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB), the three stages of the Saturn V for the Apollo 9 mission sat stacked awaiting the addition of its spacecraft undergoing final testing. Also in the VAB, workers had begun stacking the Apollo 10 Saturn V, while the Apollo 10 spacecraft arrived for testing. As the Apollo 8 and 9 crews continued their training, NASA named the crew for Apollo 10 and announced the science experiments that the first Moon landing astronauts would deploy.

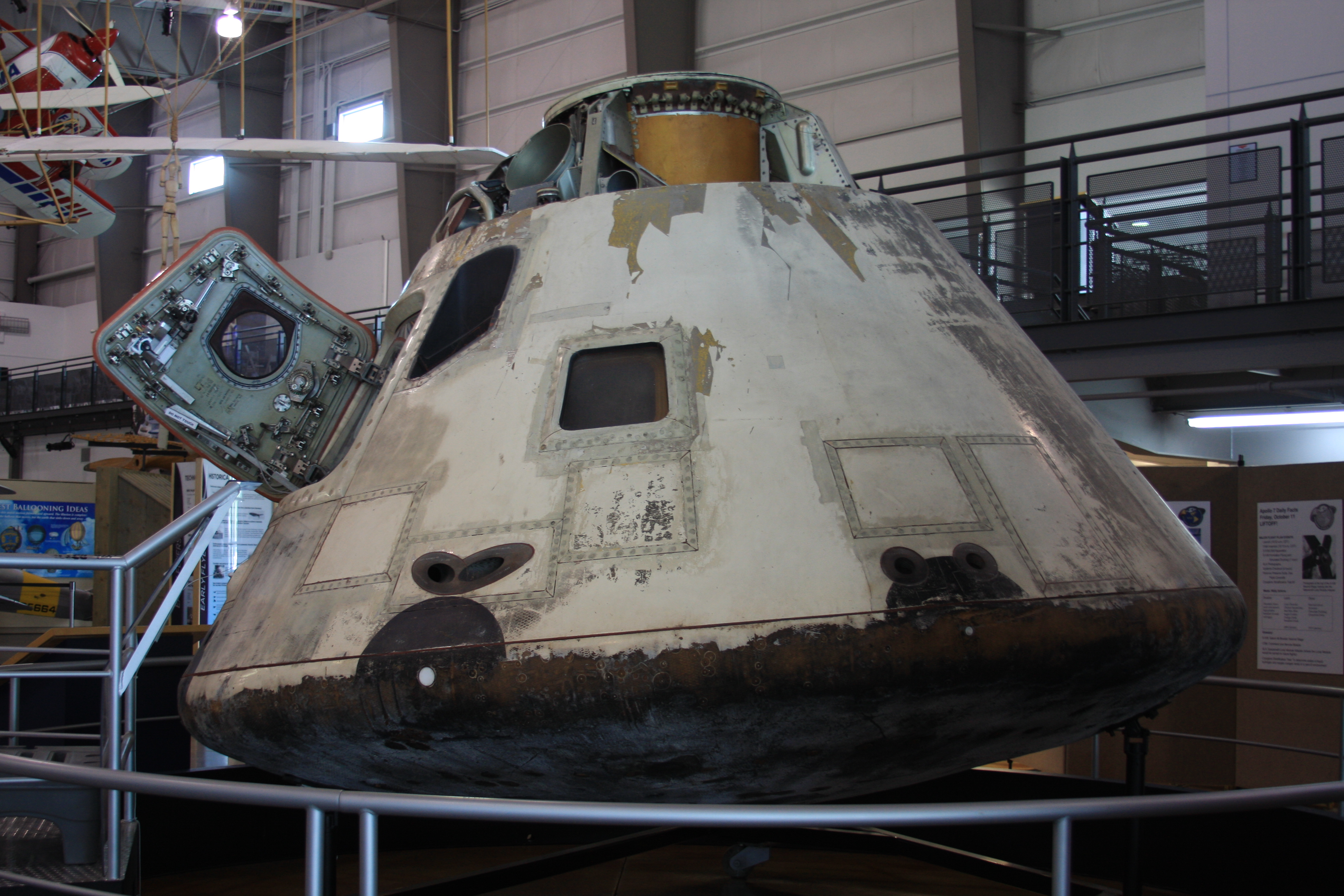

Left: President Lyndon B. Johnson, second from left, presents Apollo 7 astronauts Walter M. Schirra, left, Donn F. Eisele, and R. Walter Cunningham with Exceptional Service Medals at the LBJ Ranch. Middle: Entertainer Bob Hope, second from right, taped an episode of his show at the Manned Spacecraft Center, now NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, with guests the “Voice of Mission Control” Paul P. Haney, left, Apollo 7 astronauts Schirra, Cunningham, and Eisele, and television star Barbara Eden. Right: The Apollo 7 Command Module on display at the Frontiers of Flight Museum at Dallas Love Field.

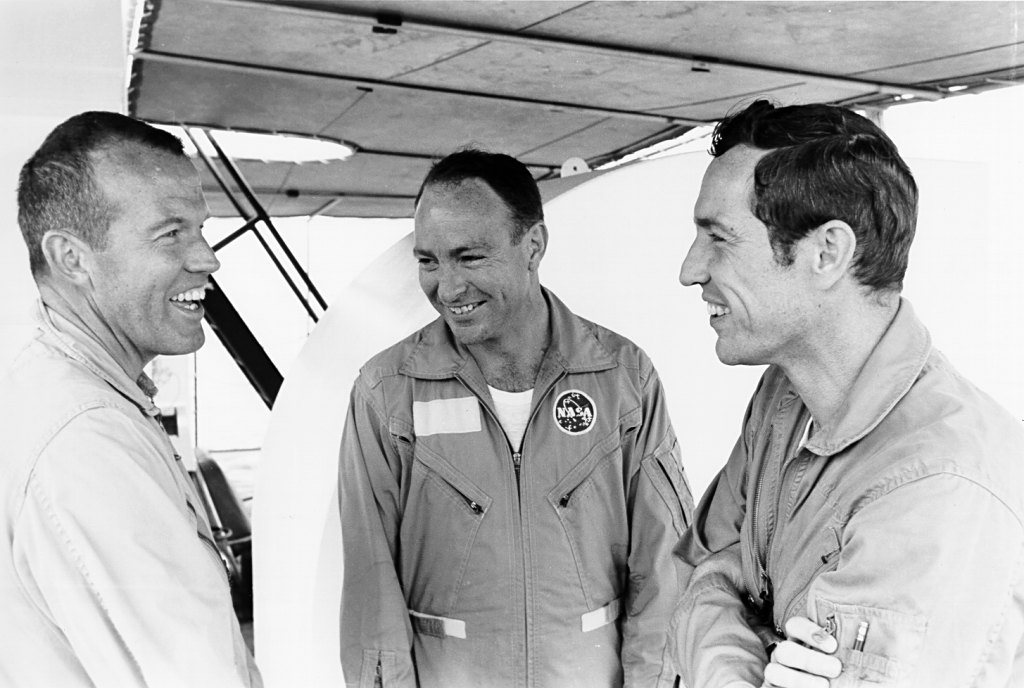

Following their highly successful flight, Apollo 7 astronauts Walter M. Schirra, Donn F. Eisele, and R. Walter Cunningham returned to Houston’s Ellington Air Force Base on Oct. 26. On Nov. 2, President Lyndon B. Johnson presented the astronauts with Exceptional Service Medals at the LBJ Ranch in Johnson City, Texas. Four days later, comedian Bob Hope filmed an episode of his weekly television variety show in the auditorium of the Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC), now the Johnson Space Center in Houston. Hope saluted the Apollo 7 astronauts in a skit that included actress Barbara Eden, star of the television series “I Dream of Jeannie” that featured fictional astronauts. Paul P. Haney, MSC Director of Public Affairs and the “Voice of Mission Control,” also participated in the skit. Following the recovery of Apollo 7, the prime recovery ship U.S.S. Essex sailed for Norfolk Naval Air Station in Virginia, where on Oct. 27 workers offloaded the Command Module (CM), and placed it aboard a cargo plane to fly it to California for return to its manufacturer, North American Rockwell Space Division in Downey, for postflight inspection. On Jan. 20, 1969, the Apollo 7 astronauts as well as their spacecraft took part in President Richard M. Nixon’s first inauguration parade. In 1970, NASA transferred the Apollo 7 spacecraft to the Smithsonian Institution that loaned it to the National Museum of Science and Technology in Ottawa, Canada, for display. Following its return to the United States in 2004, it went on display at the Frontiers of Flight Museum at Love Field in Dallas.

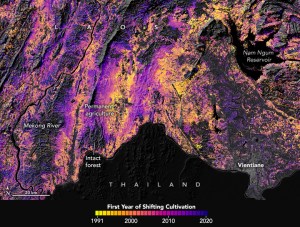

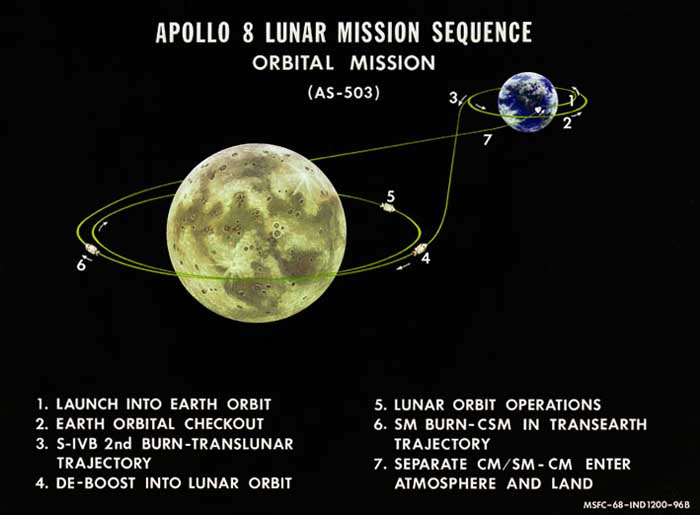

Left: The circumlunar trajectory of Apollo 8. Middle: Apollo 8 astronauts William A. Anders, left, James A. Lovell, and Frank Borman during a press conference shortly after the announcement of their mission to orbit the Moon. Right: Anders, left, Lovell, and Borman in the Command Module simulator.

On Nov. 12, 1968, NASA Headquarters put out the following statement: “The National Aeronautics and Space Administration today announced that the Apollo 8 mission would be prepared for an orbital flight around the Moon.” That momentous statement ended weeks of intense internal agency deliberations and public speculation about Apollo 8’s targeted mission. The original mission plan called for Apollo 8 to conduct the first test of the Lunar Module (LM) in Earth orbit, but when the LM fell behind schedule, NASA managers in August began contemplating sending the Apollo 8 crew on a lunar orbital test of the Command Module (CM). The decision hinged partly on a successful Apollo 7 mission, and with that milestone passed, NASA Administrator James E. Webb approved the daring plan. On only the second crewed Apollo mission, the first crew to launch on the Saturn V, and only the third launch of the mighty Moon rocket, with the second of those experiencing some serious anomalies, the decision weighed the risks against the benefits of achieving the Moon landing goal before the end of the decade. With the Dec. 21 launch date fast approaching, the Apollo 8 crew of Frank Borman, James A. Lovell, and William A. Anders and their backups Neil A. Armstrong, Edwin E. “Buzz” Aldrin, and Fred W. Haise had begun training for the lunar mission even before the official announcement. During a Nov. 16 press conference, Borman, Lovell, and Anders discussed their preparations for the historic mission. On Nov. 19, at KSC’s Launch Complex 39, engineers completed the Flight Readiness Test to validate the launch vehicle, spacecraft, and ground systems.

Left: The Apollo 9 prime crew of James A. McDivitt, left, David R. Scott, and Russell L. Schweickart, not pictured, prepares for an altitude chamber test of their Command Module (CM) in the Manned Spacecraft Operations Building at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida. Middle: McDivitt, emerging from the CM, Schweickart, at left in the raft, and Scott complete water egress training in the Gulf of Mexico. Right: The Apollo 9 backup crew of Charles “Pete” Conrad, left, Richard F. Gordon, and Alan L. Bean prepares for their water egress training.

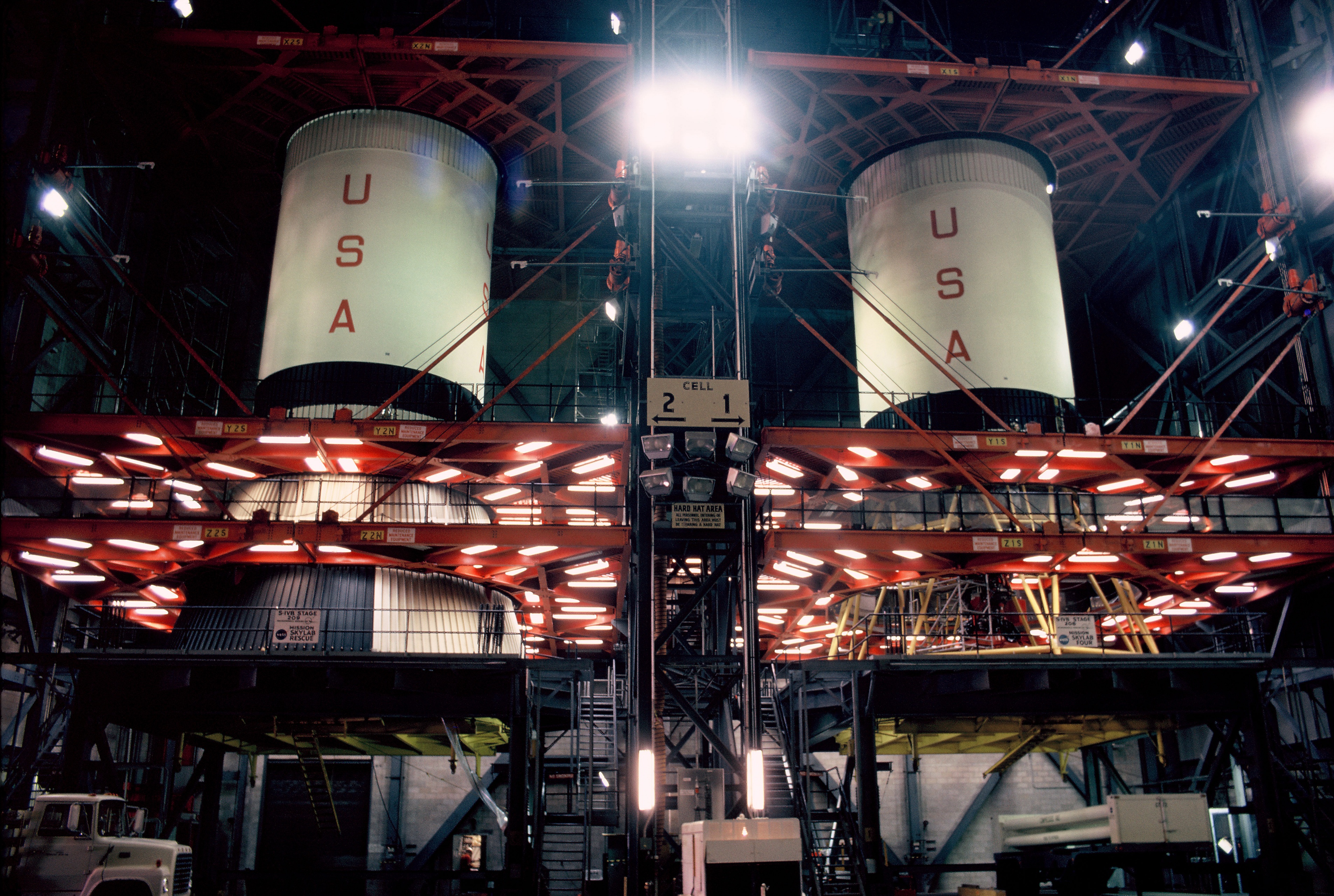

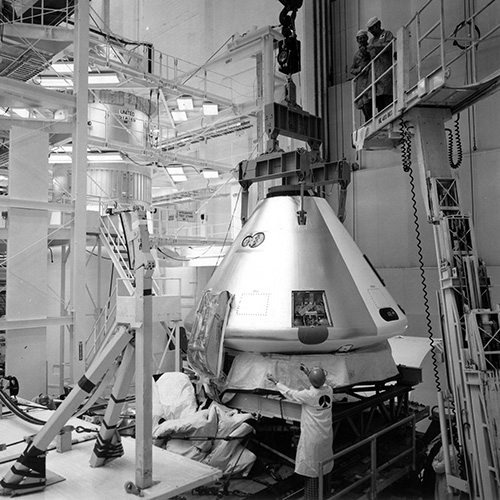

The LM formed a critical component to the Moon landing effort. Delays in preparing LM-3 for flight resulted in the crewed test to slip to Apollo 9 in early 1969. The three stages of the Apollo 9 Saturn V stood stacked on Mobile Launcher 2 in High Bay 3 of the VAB. The Apollo 9 spacecraft components, CSM-104 and LM-3, continued testing in the KSC’s Manned Spacecraft Operations Building (MSOB). The prime crew of James A. McDivitt, David R. Scott, and Russell L. Schweickart, as well as their backups Charles “Pete” Conrad, Richard F. Gordon, and Alan L. Bean completed several altitude chamber tests with CSM-104 during the month of November. On Nov. 30, workers placed LM-3 inside its Spacecraft LM Adapter, topping it with CSM-104 to complete the spacecraft for its Dec. 3 rollover to the VAB for mating with the Saturn V. McDivitt, Scott, and Schweickart conducted water egress training in the Gulf of Mexico near Galveston, Texas. On Nov. 25, workers aboard the Motor Vessel M/V Retriever lowered a mockup CM with the crew inside into the water in a nose-down position. Flotation bags inflated to right the spacecraft to a nose-up position. The astronauts then exited the capsule onto life rafts and recovery personnel hoisted them aboard a helicopter. Backups Conrad, Gordon, and Bean completed the test on Dec. 6.

Left: The Apollo 10 prime crew of Eugene A. Cernan, left, John W. Young, and Thomas P. Stafford. Right: The Apollo 10 backup crew of L. Gordon Cooper, Edgar D. Mitchell, and Donn F. Eisele.

On Nov. 13, NASA announced the crew for the Apollo 10 mission planned for the spring of 1969. The fourth crewed Apollo mission would involve the launch of a CM and LM on a Saturn V rocket. Depending on the success of earlier missions, Apollo 10 planned to test the CM and LM either in Earth orbit or in lunar orbit, the latter a dress rehearsal for the actual Moon landing likely to follow on Apollo 11. NASA designated Thomas P. Stafford, John W. Young, and Eugene A. Cernan as the prime crew, the first all-veteran three person crew. The trio had served as the backup crew on Apollo 7 and had flight experience in the Gemini program. As backups, NASA assigned L. Gordon Cooper, Donn F. Eisele, and Edgar D. Mitchell. Cooper had flown previously on Mercury 9 and Gemini VIII, Eisele had just returned from Apollo 7, while this marked the first crew assignment for Mitchell. As support crew members, NASA named Joe H. Engle, James B. Irwin, and Charles M. Duke.

Left: The Apollo 10 Command Module, left, and Service Module arrive at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida. Middle: The Apollo 10 S-IC first stage arrives at KSC’s Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB). Right: Workers in the VAB stack the Apollo 10 first stage on its Mobile Launcher.

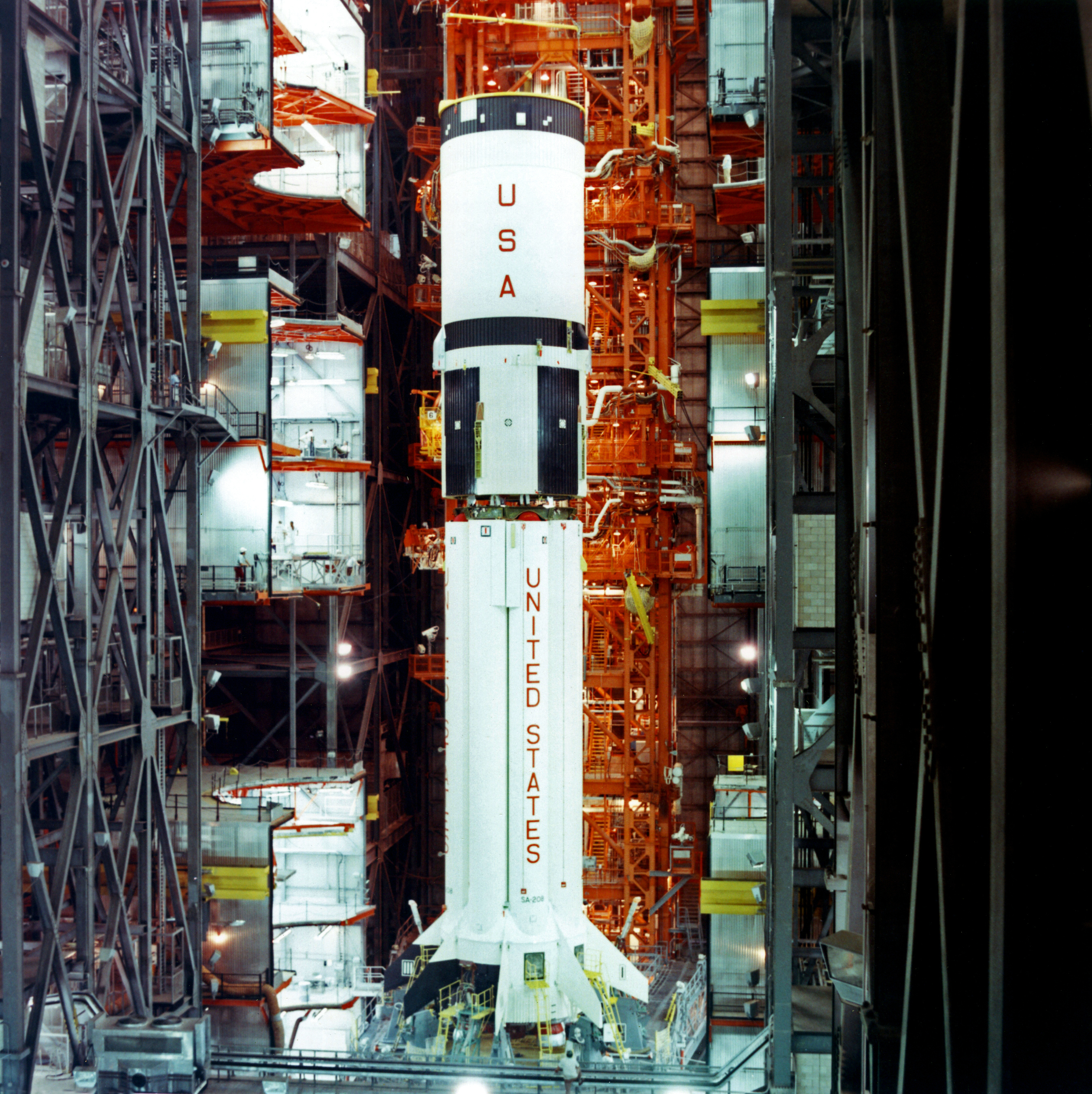

Flight hardware in support of Apollo 10 continued to arrive at KSC. Following delivery of LM-4 in October, on Nov. 2 workers mated its two stages and placed the vehicle in one of the MSOB’s altitude chambers. Stafford and Cernan carried out a sea level run on Nov. 22. The CM-106 and SM-106 for Apollo 10 arrived at KSC on Nov. 23 and workers trucked them to the MSOB where they mated the two modules three days later. In the VAB, the Saturn V’s S-IC first stage arrived on Nov. 27 and workers erected it on Mobile Launcher 3 in High Bay 2, awaiting the arrival of the upper stages.

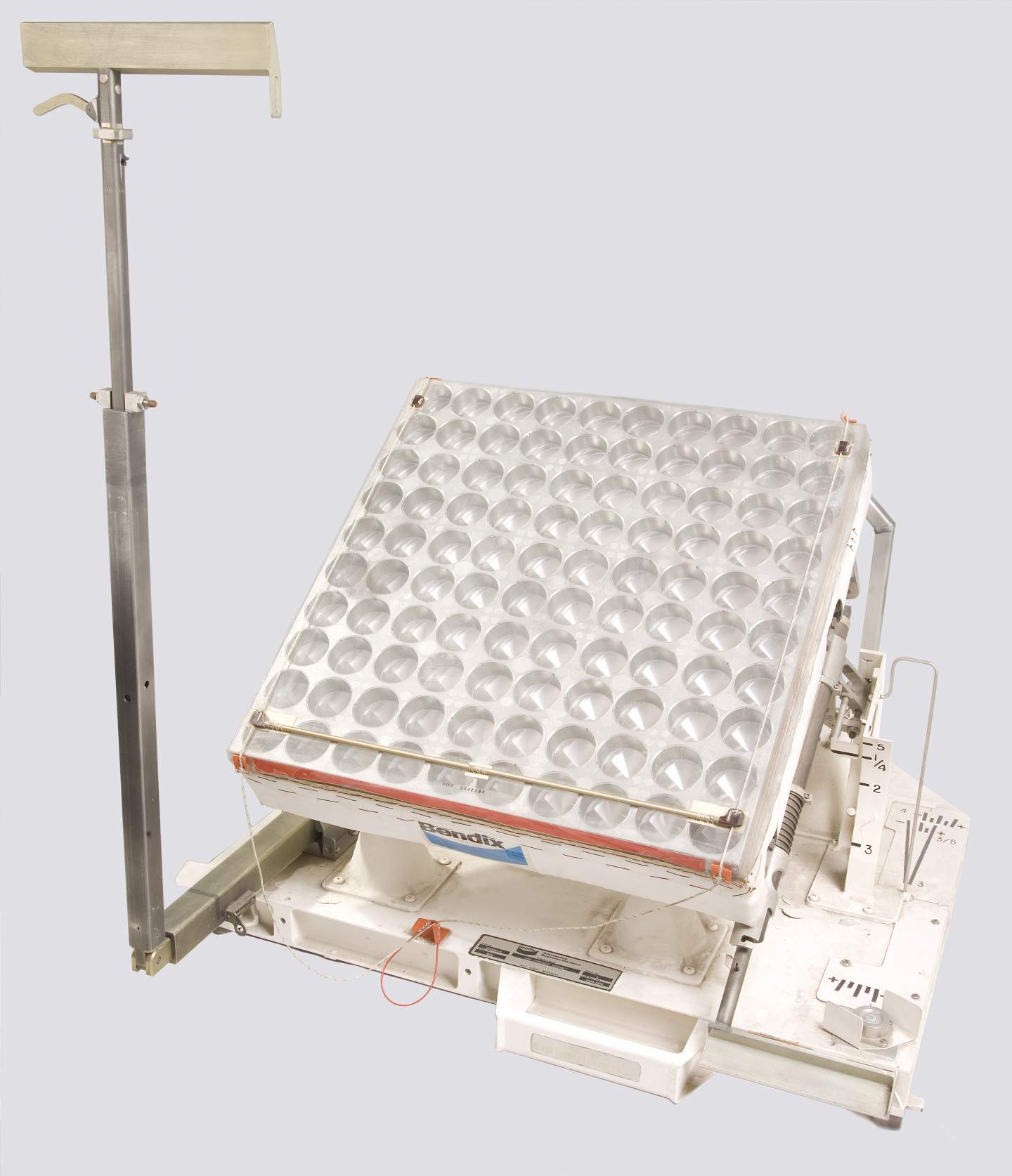

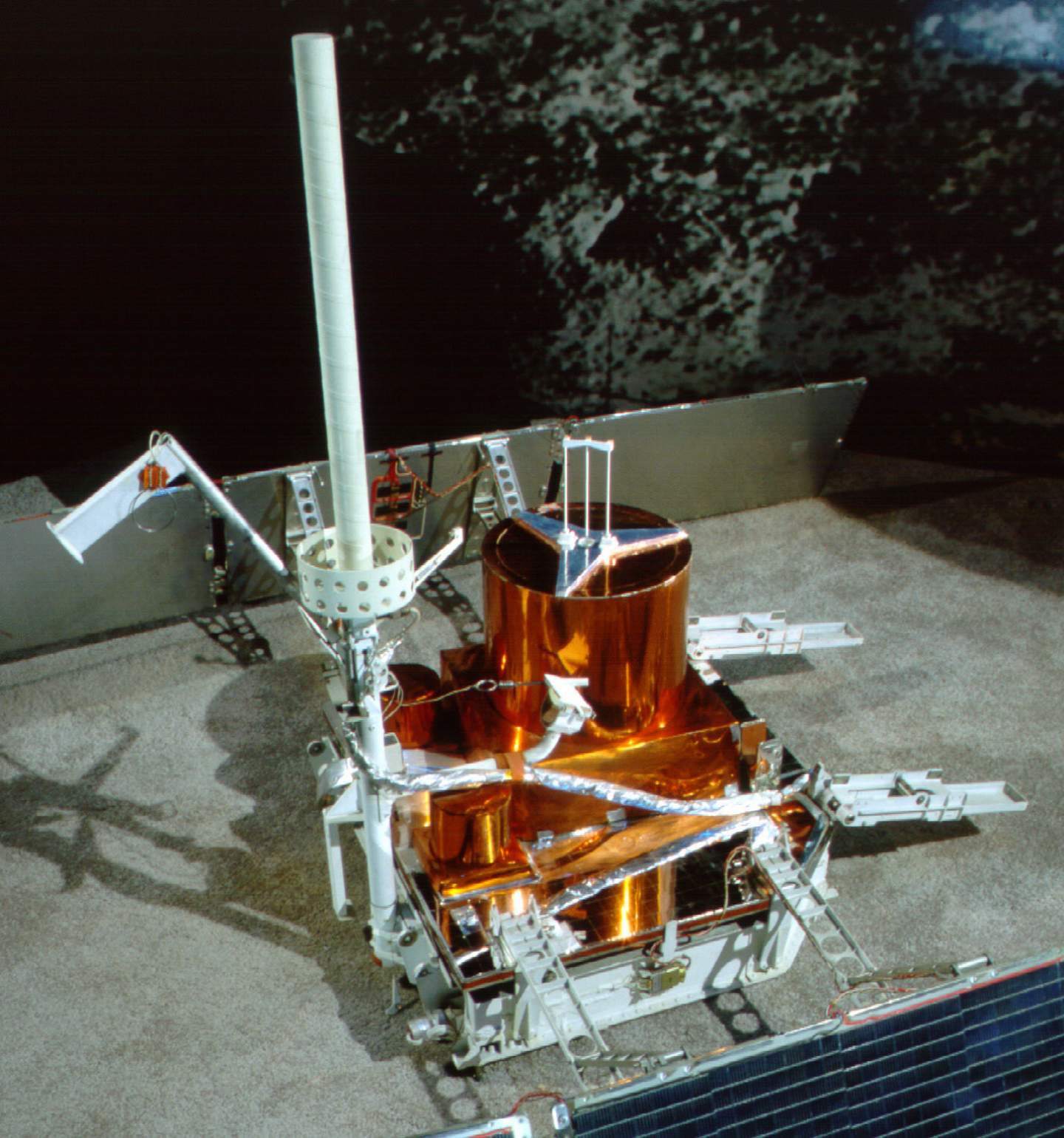

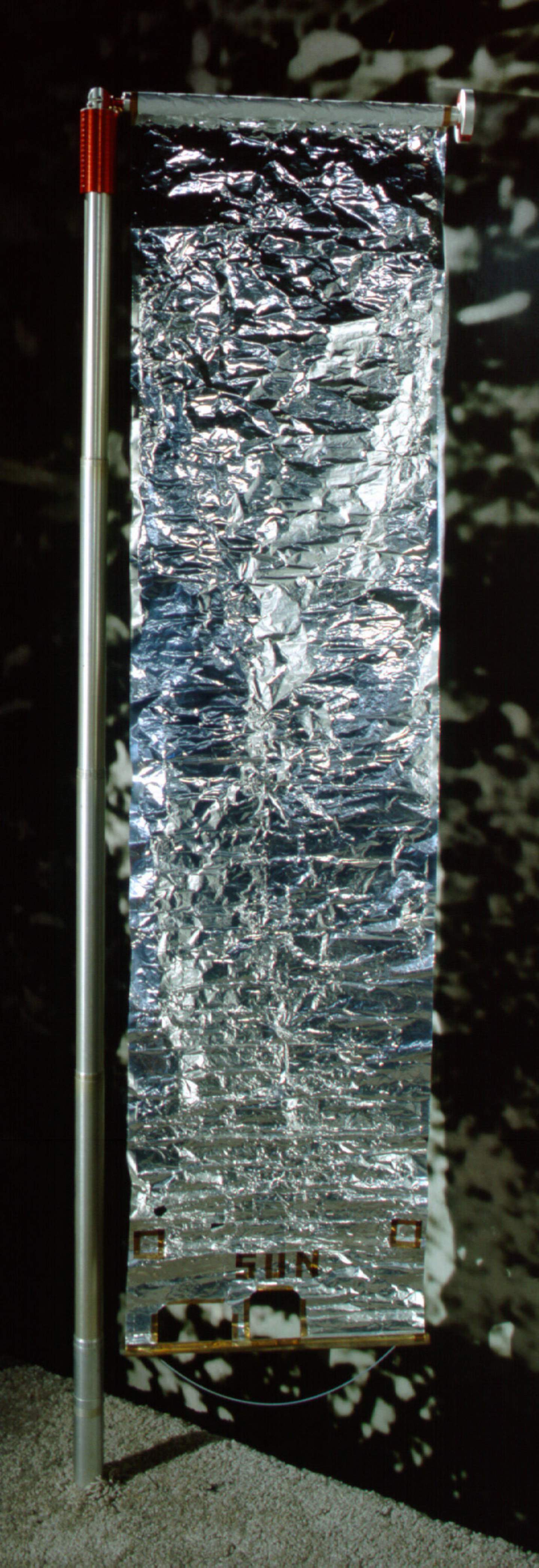

Left: A mockup of the laser ranging retroreflector (LRRR) experiment. Middle left: A mockup of the passive seismic experiment package (PSEP). Middle right: A mockup of the solar wind composition (SWC) experiment. Right: A suited technician deploys mockups of the Apollo 11 experiments – the SWC, far left, the PSEP, and the LRRR, during a test session.

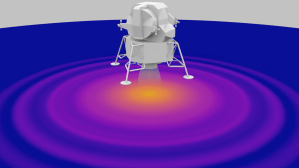

On Nov. 19, NASA announced that when Apollo astronauts first land on the Moon, possibly as early as during the Apollo 11 mission in the summer of 1969, they would deploy three scientific experiments – a passive seismometer experiment package (PSEP), a laser ranging retro-reflector (LRRR), and a solar wind composition (SWC) experiment – during their 2.5-hour excursion on the lunar surface. The PSEP will provide information about the Moon’s interior by recording any seismic activity. The passive LRRR consists of an array of precision optical reflectors that serve as a target for Earth-based lasers for highly precise measurements of the Earth-Moon distance. The SWC consists of a sheet of aluminum foil that the astronauts deploy at the beginning of their spacewalk and retrieve at the end for postflight analysis. During the exposure, the foil traps particles of the solar wind, especially noble gases.

Left: The Lunar Module Test Article-8 (LTA-8) inside Chamber B of the Space Environment Simulation Laboratory (SESL) at the Manned Spacecraft Center, now NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston. Middle: Astronaut James B. Irwin inside LTA-8 during one of the altitude runs. Right: Workers remove LTA-8 from SESL’s Chamber B at the conclusion of the altitude tests.

On Nov. 14, engineers in MSC’s Space Environment Simulation Laboratory (SESL) completed a series of altitude tests with LM Test Article-8 (LTA-8) to certify the vehicle for lunar missions. Astronaut Irwin and Grumman Aircraft Corporation consulting pilot Gerald P. Gibbons completed the final test, the last in a series of five that started on Oct. 14. Grumman pilot Glennon M. Kingsley paired up with Gibbons for three of the tests. During the tests that simulated various portions of the LM’s flight profile, the chamber maintained a vacuum simulating an altitude of about 150 miles and temperatures as low as -300o F. Strip heaters attached to the LTA’s surface provided the simulated solar heat. NASA transferred the LTA-8 to the Smithsonian Institution in 1978 and it is now on public display at Space Center Houston.

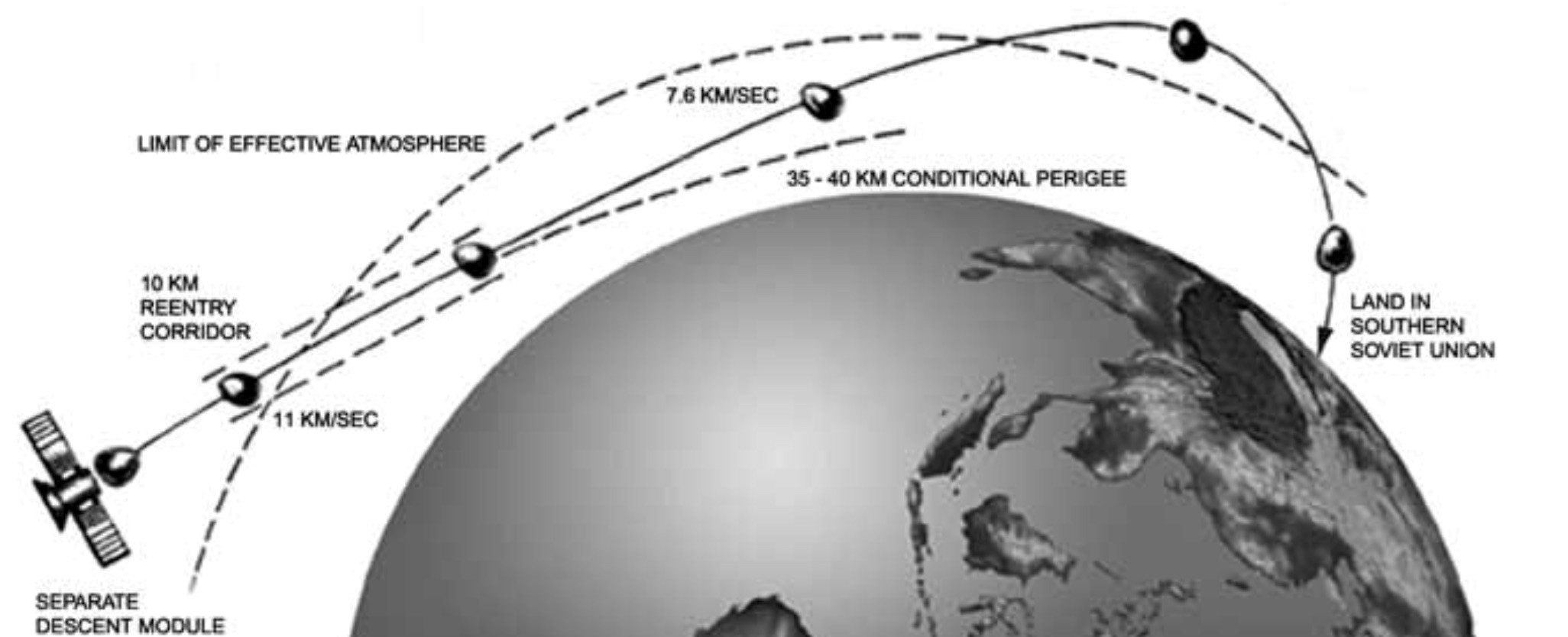

Depiction of Zond 6’s circumlunar trajectory. Image credit: courtesy RKK Energia.

Left: A Proton rocket with a Zond spacecraft on the launch pad at the Baikonur Cosmodrome. Right: Zond 6 photographed the Earth as it looped around the Moon. Image credits: courtesy RKK Energia.

Depiction of Zond 6’s skip reentry trajectory flown. Image credit: courtesy RKK Energia.

In another reminder that the race to the Moon still existed, on Nov. 10 the Soviet Union launched the Zond 6 spacecraft. Although it launched uncrewed, the Zond spacecraft, essentially a Soyuz without the forward orbital compartment and modified for flights to lunar distances, could carry a crew of two cosmonauts. A cadre of cosmonauts trained for such missions. Similar to the Zond 5 mission in September, Zond 6 entered a trajectory that looped it around the Moon on Nov. 13, passing within 1,500 miles of the lunar surface. The spacecraft took photographs of the Moon’s near and far sides and of the distant Earth. As it neared Earth during its return journey, trouble developed aboard the spacecraft as a faulty hatch seal caused a slow leak and it began to lose atmospheric pressure. Ground controllers initially steadied the pressure loss and performed a final midcourse maneuver that allowed Zond 6 to perform a skip reentry to land in Soviet territory on Nov. 17. However, the spacecraft continued to lose pressure and a buildup of static electricity created a coronal discharge that triggered the spacecraft’s soft landing rockets to fire and cut the parachute lines while it was still descending through 5,300 meters altitude. Although the capsule hit the ground at a high velocity, rescue forces were able to recover the film containers. The Soviets at the time did not reveal either the depressurization or the crash but claimed the flight was a successful circumlunar mission. With two apparently successful uncrewed circumlunar flights and the resumption of crewed missions with Soyuz 3 in October, these Soviet activities perhaps played a part in the decision to send Apollo 8 to the Moon.

News from around the world in November 1968:

Nov. 5 – Richard M. Nixon elected as the 37th U.S. President.

Nov. 5 – Shirley A. Chisolm of Brooklyn, New York, becomes the first African American woman elected to the U.S. Congress.

Nov 8 – The United States launches Pioneer 9 into solar orbit to monitor solar storms that could be harmful to Apollo astronauts traveling to the Moon.

Nov. 13 – The HL-10 lifting body aircraft with NASA pilot John A. Manke at the controls made its first successful powered flight after being dropped from a B-52 bomber at Edwards Air Force Base in California’s Mojave Desert.

Nov. 14 – Yale University announces it is going co-ed beginning in the 1969-1970 academic year.

Nov. 22 – The Beatles release the “The Beatles” (better known as the White Album), the band’s only double album.

Powered by WPeMatico

Get The Details…

Kelli Mars